He will take care of everything, but will do all under the abbot’s orders.

How then shall we live?

I have been a public critic of the isolated, CEO-styled leadership within the church for many years. Even when a leader ‘builds a team’ around them it can remain under their power and responsibility; no decision of any importance is made without them knowing of it. It seems sensible enough: if the buck ends with you, you’d want to be aware of the risks. A church can be a large ship and, therefore, needs decisive and visionary captains to steer it through decisions and strategies. This cannot be done through committee as disagreement costs time and and can divert the ship off course to their ultimate goal. With this understanding of ministry the pyramid structure of leadership is the most efficient and effective.

What if that wasn’t the aim of Christian ministry? What if the church wasn’t meant to have a five year plan because it had an eternal plan? What if the plan was not to have a militaristic styled strategy of ‘take-over’ the world because the plan was to simply live as if this world was of no threat in the light of the resurrection? What if the church was meant to be a gathering of people who were committed to living more like Jesus together and establishing a Kingdom which played by completely different rules to that of the world in which they find themselves?

In this sort of community there is no need for a head because the direction is not one person’s possession which he/she allows others to be a part of but the direction is set by a Spirit which is discerned collectively and owned collectively. In this model the community is like a family. What kind of family sits down and discusses their five year plan? Would they choose, at a family gathering, which of them is going to ‘lead’ the family? Is a father more important than a mother, one sibling more important than another? The one who cooks, are they deemed more responsible than the one who washes up?

In the Rule of St. Benedict, the role of the abbot is clearly a ‘leader’. I’ve read many articles, theses and books that use the role of the abbot in a monastery as a model for spiritual leadership and I’d agree with most of them but what is interesting is the role of cellarer; are they a leader or not? if a leader then a lesser one than abbot? The cellarer is under the authority of the abbot, for sure; it clearly says that but what kind of authority does the abbot wield over the cellarer? A humble oversight of the spiritual health of each and every monk. The role of the abbot is to ensure that, on the Day of Judgement, the monks can stand before God pure and holy in his sight. The spiritual health of the monks will be the measure of the abbot’s faithfulness to Christ. It is a heavy responsibility. The abbot is a teacher of the faith,

he should show them by deeds, more than by words, what is good and holy.

The abbot is an overseer and is entrusted with the task of ensuring the ethos and character of the community is that of Christ. He is not to be the decider of action; that is left to others. Although there is a complex relationship between character and action there is a distinction between the two. Whether our actions drive our character or the other way round it is clear that character is ‘being’ and action is ‘doing’.

I saw this this week and it made me smile!

In this understanding the abbot is the overseer of the community’s ‘being’ but it is the role of someone else to oversee the community’s ‘doing’. In St. Benedict’s understanding the ‘doing’/action must come from the ‘being’/character but it is not his role to decide what that ‘doing’/action is. The abbot establishes a partnership with others. This partnership is entered into by humble servants who are focussed on the weight of their respective roles. They must not be mistaken that their role is the highest but rather the lowest being always aware of the fallen nature of humanity and the insurmountable, unending task that lays before them; how to be the Body of Christ in the world.

The monastic call has always developed in times and places when the church is asking one question,

How then shall we live?

In the dust clouds of the falling worldly empires and structure, godly men and women have fled to the edge lands and asked this question. This question has led these gathered survivors first to silent mourning,confession, repentance and prayer; in this they strip themselves of the ways in which they were caught up in the dying empire and dismantle the inner constructions of the empires within themselves. After this confession and repentance they begin, slowly, to live out the basics of faith; to live simply, not to complicate things or move quickly. At each step they ask this one question. How do they discern what is right and wrong? by asking ‘Does it look like Jesus?’

Looking like Jesus is a character issue – pure and simple.

In order to answer, ‘What Would Jesus Do?’you must first ask ‘What Is Jesus Like?’; it is easier to decide what to do if you know what it is you want to be.

How easy it is to say,

Just be like Jesus.

But we all have a different understanding of who Jesus is… This is where the community becomes the most important factor: The Spirit of God points to Jesus and leads the people of God to know Christ and Christ crucified. It is the Spirit that tells us “Jesus Christ is Lord”. The Spirit moves in the Body of Christ not in one part of it. The Spirit is the life blood of the Body and flows to each part giving vitality and movement/action.

Wisdom and discernment takes time for us fallen humans but we are nowhere without it. We are like all other empires and worldly groups doing lots and being nothing. St. Paul has this advice to a Christian community,

Do nothing from selfish ambition or conceit, but in humility regard others as better than yourselves. (Philippians 2:3)

“Do nothing,” says Paul, “from a place of ‘electioneering’ or when you are focussed on your office, nor empty pride, but, from a place of knowing of what you are made and to what you can quickly return to, lead others to be superior to yourself.” It is interesting that what is translated here in NRSV as ‘regard’ is the greek word ‘hegeomai’ which means ‘to lead’. Don’t move until you have the character and the Spirit directs you.

In the theatre an actor is given a character, then they are given a space in which to perform and to play, then they move and are shaped by the director. It’s a beautifully creative and surprising activity of playing and moulding. The same is true of the spiritual work of faith; we need to get to know the character, through reading the script. Then we attempt small movements and vocal trials all the while looking to the director for guidance and encouragement. In an ensemble model of theatre practice the director is not the dictator but a fellow artist; their role is to observe and ask questions. In the spiritual work the director is the Holy Spirit who prompts, challenges and encourages us to become more and more truthful portrayers of the character of Christ.

Reflection

Parish ministry is set up so the minister is the management and the spiritual director although they are different tasks and roles. As the leader with sole responsibility you are called upon to not only have oversight of the spiritual wellbeing of your community, vast and varied as that is, but also to make decisions as to what sermon series to do, organising events, setting up for services, making sure the rotas get done, managing PCCs with all the bureaucracy and business.

Imagine what could be achieved if the day to day running of a parish was established as a different role to the role of spiritual guide? I wonder what that might look like. Imagine if that was the expectation.

What I mean is, what if ‘leadership’ roles was more like St. Paul’s use of it in Philippians 2 as the raising up others and not drawing attention to the office. That discipleship was the desired office to have and the model of ministry was structured round the development of discipleship.

Heavenly Father, you call us all into your kingdom to be transformed into the character of Christ. help us by your Spirit to be formed daily into his likeness. May our actions reveal his character and may his character inform our actions that all of our being will reveal him to the world, for your glory!

Come, Lord Jesus

Who has the right to the land of Gaza and the West Bank? We could start by going into all the history and legalities over this issue. The use of words such as ownership can then be brought into question. Historical facts could then be muddied by interpretation of events and phrasings and then there’s the insurmountable obstacle of personal stories and the tangled web of historical violence from both sides.

Who has the right to the land of Gaza and the West Bank? We could start by going into all the history and legalities over this issue. The use of words such as ownership can then be brought into question. Historical facts could then be muddied by interpretation of events and phrasings and then there’s the insurmountable obstacle of personal stories and the tangled web of historical violence from both sides. Winning arguments is easy if you can just wear down your opponent and the easiest way to do that is keep moving the goal posts; re-define the terms of the argument until it gets too complicated and they get confused and worn out. You don’t need truth to do this; all you need is stamina and intelligence.

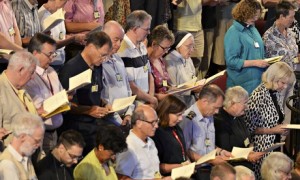

Winning arguments is easy if you can just wear down your opponent and the easiest way to do that is keep moving the goal posts; re-define the terms of the argument until it gets too complicated and they get confused and worn out. You don’t need truth to do this; all you need is stamina and intelligence. In November 2012 General Synod’s motion to vote female bishops failed, only just but enough. What was clear back then was that the debate had been established on the principle that there was an ‘us’ vs. ‘them’. The aim was not to discover wisdom but to ‘win’ at any cost. Both parties on the extremes didn’t seem to care how they would win just as long as they did. This week, however, the tone of the debate was not on winning points and persuasion but a genuine, heartfelt desire to seek wisdom and to trust one another. The debate stopped being about party politics but more about seeking genuine peace and wisdom only found in the Spirit of God.

In November 2012 General Synod’s motion to vote female bishops failed, only just but enough. What was clear back then was that the debate had been established on the principle that there was an ‘us’ vs. ‘them’. The aim was not to discover wisdom but to ‘win’ at any cost. Both parties on the extremes didn’t seem to care how they would win just as long as they did. This week, however, the tone of the debate was not on winning points and persuasion but a genuine, heartfelt desire to seek wisdom and to trust one another. The debate stopped being about party politics but more about seeking genuine peace and wisdom only found in the Spirit of God. To dismantle such a fence of division takes time, building trust and relationship something sadly lacking in our politics in this country. My very public critique of the Same Sex Marriage Bill was not based on some personal, moral judgement on homosexuality but on the way a decision was being sought. It was rushed. The lobbyists pressured opponents with the supposed lack of time and bullied people into making a response; to choose a side of the fence. Rather than taking the fences down they were happy to keep them there. People were forced off the fence onto one side or the other and it was all done by the manipulation of language. The same is being done with The Assisted Dying Bill.

To dismantle such a fence of division takes time, building trust and relationship something sadly lacking in our politics in this country. My very public critique of the Same Sex Marriage Bill was not based on some personal, moral judgement on homosexuality but on the way a decision was being sought. It was rushed. The lobbyists pressured opponents with the supposed lack of time and bullied people into making a response; to choose a side of the fence. Rather than taking the fences down they were happy to keep them there. People were forced off the fence onto one side or the other and it was all done by the manipulation of language. The same is being done with The Assisted Dying Bill.