Conversations are broken

So begins the blurb on the back of Nihal Arthanayake’s new book ‘Let’s Talk: how to have better conversations’. I picked up Arthanayake’s book whilst on holiday and devoured it within a few days. It was a timely read for me as I continue to imagine what is being shaped at Bradford Cathedral in the run up to City of Culture. We have articulated aims at the Cathedral to “be a place where challenging issues facing the world can be discussed and debated openly and safely” as well as being recognised “as the safe place for gathering when local or global events require a spiritual response or an honest conversation.”

So what makes for good conversation? Why is the art of disagreement such a popular idea at the moment? From ‘The Rest is Politics’ podcast’s stated aim “to disagree agreeably” to the Church of England’s repeated mantra to learn to “disagree well”; lots of people are trying to recapture the skills to debate safely in an increasingly polarised world. Public discourse has lost a sense of maturity, calmness and creativity. We can point fingers towards the rise in social media (or, should we call it unsocial media?) or the cuts to education which disproportionally impact the humanities and thus our ability to learn the empathetic imagination required to converse with people of difference. There are, however, many other factors that have led to the erosion of social cohesion and community integration. The Covid 19 pandemic didn’t cause this conversational decay but it has undoubtedly accelerated the degradation of all the skills required to interact with others.

This month we have held 3 events at Bradford Cathedral that I have helped to produce, all aimed, in different ways, to position us as an organisation to fulfil the aims stated above. Each of these spaces, in different ways, used the arts to inspire and/or hold difficult, contested views in the hope of discovering, with people of difference, a new way forward together.

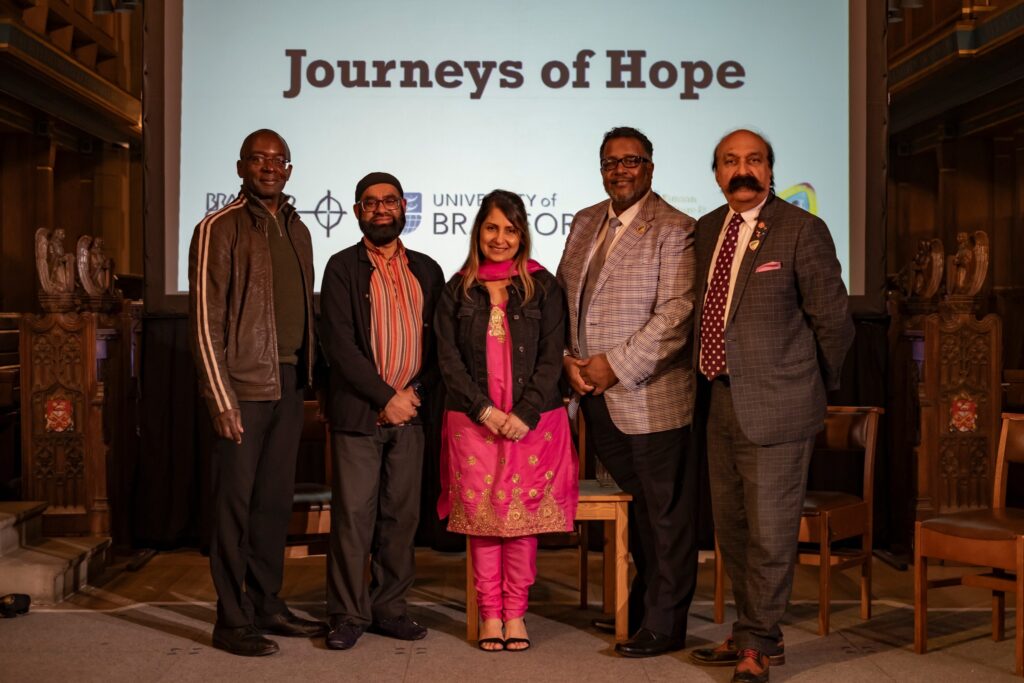

‘Journeys of Hope’ was an exhibition that told the stories of both the Ugandan Asian diaspora, who travelled to Britain in 1972 after being expelled from their homeland by Idi Amin, and ‘the Windrush generation’, who arrived from the 1940s seeking to fill labour shortages after World War II. As part of our engagement in ‘Black History Month’ we wanted to hear different black histories alongside one another to discern the universal experience as well as the nuanced and distinct narratives from different ‘black communities’. The banners that made up the exhibition depicted, in word and pictures, the journeys made by these different migrant communities. The public were invited to engage in the dialogue between the two different narratives.

The launch event amplified the voices from these two particular communities of Bradford. Individuals talked about their experience of having multiple ‘homes’ e.g. both the Caribbean or Uganda and Britain. The contributors began to explore together what they understood by ‘identity’ the painful memories that have shaped them as well as the joyful realisations they have discovered. I chose to give space for those stories, particularly the painful parts to just hang in the air. The silence inviting us to face the uncertainty without the pressing need to respond immediately; to ‘befriend’ the emotions that were stirred.

In the press coverage surrounding the exhibition the media were most interested in the deliberate shift we are making in Bradford from talking about multiculturalism to interculturalism. Multiculturalism carries connotations of a kind of deceptive ‘tolerance’; a meagre allowance of another’s existence. It rarely inspires any creative interaction and, indeed, I would, in some small way, agree that “multiculturalism is dead”. I do not see how this acceptance of the other in my periphery as doing anything beneficial and will, with little encouragement, fall into ghettoisation and conflict. Interculturalism, on the other hand, invites ‘inter’action between cultures. It means, as one local, Bradfordian broadcaster said at a recent Religion Media Conference hosted in our city, “getting up in each other’s business.”

Secularists would have us all believe that the public realm is a naturally neutral space. This is not true. There is no such neutrality because it is always curated by a particular worldview, most often a secularist’s. A healthy and honest public space that encourages healthy, creative conversation around shared political and social goals is hard built and even harder to sustain. Intercultural practice, as opposed to multiculturalism, requires particular skills which are not obvious or easily learnt. One principle is deep, empathetic and imaginative listening. I explore this and a complimentary principle of ‘overaccepting’ in an article soon to be published in the Oxford Journal of Intercultural Mission, entitled, ‘Improvisation as Intercultural Practice’. Essentially I argue that the skills that make improvisatory drama work are the same that make public discourse work: curiosity and mutual trust. This is what is lacking so often in our interactions with others.

We were also invited, by the Council, to host an ‘interfaith service’ to begin Hate Crime Awareness Week. This year’s theme was tackling religiously motivated hate crime. Because interfaith worship/prayers are more complicated than many understand, I decided to invite friends from different faiths an opportunity to share, from a personal perspective, what their particular faith teaches them about relating well across religious difference. This kind of sharing can easily descend into a kind of Faith Battle as individuals feel they must ‘represent’ and defend their position. It was specifically to counteract that temptation that I encouraged contributors to speak only from their personal view and followed it with silence, reflection and, if the congregation wished, to pray privately. This approach disarmed the pressure we put upon ourselves when we talk publicly about a deeply held, identity shaping thing such as faith. It encouraged people to simply accept the offer being made with no need to respond either affirmatively or negatively.

The event was held on 16th October, just 9 days after the atrocities seen in Israel and the subsequent heartache across the region as Israel and Gaza fell again into bloody conflict. This event was naturally overshadowed by the pain, confusion and anger felt by many in our community in Bradford and across the world. Fortunately I had already devised a creative way that we could stand together as people of different faiths in a meaningful way without using words that can regularly, particularly at such times of heightened hostilities, get taken out of context, misheard/misunderstood. We simply lit a single candle from individual candles representing our different faith traditions. We held silence together and allowed one another to lament and be baffled together without requiring a verbal response.

Sometimes the skill of conversation is knowing when not to speak.

Finally we hosted a delegation from one of our Diocesan links. Bradford has partnered with the Church District of Erfurt in Germany for over 30 years. We have regularly engaged in an exchange programme: us visiting them and they us. This year it was their turn to come over to us. As we devised an event at the Cathedral we discovered it had been 90 years since Dietrich Bonhoeffer visited Bradford and made, what became known as the Bradford Declaration. It was the start of the work that culminated in the much wider known Barmen Declaration which spoke against the Nazi regime and led, ultimately, to Bonhoeffer’s arrest and death in 1945.

In honour of this anniversary we decided to host an event that helped us to reflect on the role of faith in politics and politics in faith. We had three speakers: Dr Matthias Rein who is a Lutheran pastor in Germany who gave us a good background to Bonhoeffer and his ongoing legacy in Germany in 21st century, Revd Dr Noel Irwin, a Methodist Minister who teaches community development and organising, political and public theology who spoke about the impact of Bonhoeffer’s thoughts on violence/non-violence during the Trouble in Northern Ireland and Rt Revd Nick Baines, bishop of Leeds who talked from his experience of being a bishop in the House of Lords. Tough questions were raised and some complex ideas began to be unpacked.

Again, in the media interviews I engaged with they focussed on the common request that people make to ‘keep faith out of politics’ or ‘keep politics out of faith’. In the light of the Israel/Gaza situation and the overwhelming complexities involved in that historic, multifaceted issue, such requests are, in my mind, naive and reckless. Whether you ascribe to a particular shared religious doctrine or are not part of an organised expression of belief we all believe in something. This is either a spiritual, political or psychological idea or, most likely, some mixture of all three. There is some set of values which coalesce into some form. This is your faith. This shapes your decisions and choices. Those choices direct your actions and engagement in the social world. This is politics. It is, therefore, dishonest, to suggest that anyone can separate their faith/beliefs from their political choices.

The event was held within the context of a bilingual choral evensong. I had thought that many would only turn up for the intellectual part of the evening but in fact we had all 80 or so audience members from various backgrounds come and experience the sung liturgy which included prayers of Dietrich Bonhoeffer. The music, I felt, played a significant part in settling people into our time together and expressed in the hauntingly beautiful harmonies the complexities Bonhoeffer faced in his time. In our own time, as demands are made on us to make choices and to pick sides, I listened to the quartet of voices sing words of trust often creating deliberate dissonance in the melody. I was reminded of a contemporary of Bonhoeffers, Karl Barth, who once wrote,

And he who is now concerned with truth must boldly acknowledge that he cannot be simple. In every direction human life is difficult and complicated… Men will not be grateful to us if we provide them with short-lived pseudo-simplifications.

Karl Barth, The Epistle to the Romans (Oxford: Oxford Univeristy Press, 1968) p.5

Arthanayake, referring to words spoken by Professor Tanya Byron earlier in his book, concludes by saying,

…we must make sure that our education system encourages rather than diminishes curiosity. The curious may well dive into the online world to find answers to questions they have, but they will also wish to discuss those answers, refine them and even have them changed by new advice or evidence. The curious will have their ears open to empathise with the experiences of others or to process and push back on opinions they do not agree with. The curious will talk to strangers.

Nihal Arthanayake, Let’s Talk: how to have better conversations (London: Trapeze, 2022) p.266

That curiosity should be directed towards deliberately shaped silences in the world around us in order that we can engage better with to the daunting silence we find within. The arts should curate public spaces of silence to invite us, to woo us, into the uncomfortable conflicts that lie within us all so we can hold firm in the conflicts outside. When people declare our silence as deafening or that non-words are hurtful I weep. It’s because they cannot feel the gift that shared silence can be.