It was during my sermon on the story of the resurrection appearance to Thomas (known also as the twin) that I became aware of our culture’s view on doubt. It was with great ease that I was able to tell people I was preaching on ‘Doubting Thomas’ and the acceptance of that concept was widespread enough that it revealed a cultural reference point. In my sermon I asked why this one disciple was now infamous with doubt when it is clear that each of the close friends of Jesus doubted the reality of the resurrection before they saw the proof? Why, I thought, do we identify Thomas with this one event when he went on to be a great, faithful apostle in India (many believe!)?

As I explored this question with the congregation on Sunday morning, I began to think about my own underlying language about doubt; the name ‘Doubting Thomas’, amongst many, is assumed as an insult of some kind. To be identified with doubt is to be identified, in the original intention of the name, with weakness and failure. Doubt, it is felt, is wrong.

Traditionally doubt was the direct opposite of faith. Faith is our goal, therefore doubt is the antithesis of that. This leads to doubt being frowned upon and something to be dismissed. There is, however, a change to this view for some. It is more acceptable now to discuss doubt in more positive light, doubt has become ‘part of the life of faith.’ In some circles, however, it has become even more than that. Doubt is either still spoken of in terms of something we live with but still not to be focussed on or it is at the heart of what we’re about. This latter view is the central tenants of Peter Rollins’ theology (‘To believe is human. To doubt, Divine.’)

I think both of these new viewpoints are interesting but have faults with them. The first view acknowledges the presence of doubt but it is seen as something to forget or to not pay attention to and, as you mature in faith, those doubts will disappear, revealing potentially other doubts about other aspects of the life of faith and God. The issue with this is doubt becomes an irritant whose solution is time. The second view not only acknowledges doubt but actively welcomes and encourages it as an important aspect of the walk of discipleship. I can see great benefit in this and we should not shy away or try and dismiss doubts. I am cautious, however, in my reading of Rollins, et al. who seem to be saying that it is the centrality of the Christian faith. That Jesus’ experience of doubt and forsakenness on the cross, expressed in his statement, ‘My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?’ is the gospel, jars with me (in both a good and an unhelpful way.)

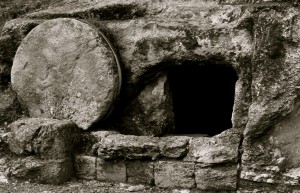

On Resurrection Sunday, I preached a sermon on the empty tomb and proposed that we can fall into the trap of staying at the empty tomb; we can get caught up in the empty tomb and be so amazed at it’s emptiness that we forget the real wonder of that day (This was an unashamed re-working of Thomas Merton’s reflection in his book ‘He Is Risen’). The empty tomb, I suggested, is just a signpost to the real thing. It is not the empty tomb we worship, it is the risen Lord. I likened this to gathering round a signpost for Yorkshire and celebrating as if we had arrived in God’s own country (I apologise to those heretics who do not accept this truth to be self-evident!)

On Resurrection Sunday, I preached a sermon on the empty tomb and proposed that we can fall into the trap of staying at the empty tomb; we can get caught up in the empty tomb and be so amazed at it’s emptiness that we forget the real wonder of that day (This was an unashamed re-working of Thomas Merton’s reflection in his book ‘He Is Risen’). The empty tomb, I suggested, is just a signpost to the real thing. It is not the empty tomb we worship, it is the risen Lord. I likened this to gathering round a signpost for Yorkshire and celebrating as if we had arrived in God’s own country (I apologise to those heretics who do not accept this truth to be self-evident!)

I want to suggest this second approach to doubt has the potential to trap us like the empty tomb does. We can get focus so much on achieving or experiencing doubt that it becomes the destination. We want to be identified with doubt. Once we arrive there we feel we’ve made it and we warmly embrace it and it becomes a comfort in it’s own way: ‘as long as we have doubt we know we’re ok.’

Doubt in the story of the disciples after the resurrection is only ever a stepping stone to faith in the risen Lord. Thomas does not remain a doubter (or at least not in that way.) Jesus says to him,

Stop doubting and believe.

To which Thomas responds,

My Lord and my God.

He moves from doubt to a positive profession of faith. This is a move which many in my generation struggle with. We are a people who are addicted to doubt and reactionary rebellion. This rebellion against accepted norms and traditions are often good and necessary but we get stuck in that idealistic place of protesting against a system or ideology but we never seem to be able to work out what we do stand for. We are passionate about what we don’t believe in or feel comfortable with or what is unjust but we have little to stay what is right and when we do find it we struggle to articulate it out of fear that our peers will disagree and we will become the focus of their protests.

Can community be built on doubt? The passion and emotions involved in questioning all we see only lasts so long and sooner or later there needs to be foundations or otherwise the sifting sands will swallow us and we sink. Doubt isolates us from others in a profound way and, without being careful, we exclude others in our doubts. What can be shared if you affirm nothing? If all you affirm is doubt what happens when those doubts are reconciled? If doubt is the central tenant of a community you are a part of, then how and when can celebration occur?

This is not to say that we err the other way and firmly fix our dogmas and ensure people sign up to our set doctrines but there needs to be an affirmation of doubt without it being the destination we’re aiming for. The empty tomb is necessary but only as that which propels us on to meet with the risen Lord. Doubt is necessary but should only be seen as that which propels on to find faith in the risen Lord.

As I see the end of my time in London taking large strides towards me like a long awaited loved one, their arms wide open to embrace me, I am struck by the loud crashes behind me forcing me to look back. I am stuck now between turning and embracing the rest and peace after a long a difficult journey and the need to see the explosion behind me to ask “Was that me?” On my journey I have, like all journeys, made decisions to take certain paths and they have all been made with honesty of the situation and with integrity. My decisions have effected people and situations and not all of them were positive.

As I see the end of my time in London taking large strides towards me like a long awaited loved one, their arms wide open to embrace me, I am struck by the loud crashes behind me forcing me to look back. I am stuck now between turning and embracing the rest and peace after a long a difficult journey and the need to see the explosion behind me to ask “Was that me?” On my journey I have, like all journeys, made decisions to take certain paths and they have all been made with honesty of the situation and with integrity. My decisions have effected people and situations and not all of them were positive.