I rarely write a script for my sermons but due to the contentious issues raised during this one I felt I needed to. Many people have asked to see a copy and so I publish it here in full.

The reading for the day was Matthew 13:24-30, 36-43

(It also is inspired by the epistle as well: Romans 8:12-25)

This week has seen several momentous debates take place. It started with the Church of England’s General Synod discussing the issue of allowing women to become bishops and finished with the House of Lord’s debating the controversial ‘Assisted Dying Bill’. It has been a week of heated opinions and difficult conflict. To add to these there’s also been renewed conversation around the Israel/Palestine conflict to manoeuvre. All in all it could have left many of us feeling overwhelmed and confused.

Which side do I stand on?

How do I know what is right and wrong?

Who can I trust?

I wouldn’t blame anyone for just keeping your head down and not engaging because it’s tiring, isn’t it?

![]() When I was at school we often staged debates on moral and ethical issues. These debates were put on to help us to develop our persuasive writing technique and for this reason I was always quite good. You see, to succeed in a debate you must defeat your opponent’s argument and not, necessarily, with facts. Most of the time they were won by playing with language. If you can bring into question the use of a word you can subtle destabilise any argument.

When I was at school we often staged debates on moral and ethical issues. These debates were put on to help us to develop our persuasive writing technique and for this reason I was always quite good. You see, to succeed in a debate you must defeat your opponent’s argument and not, necessarily, with facts. Most of the time they were won by playing with language. If you can bring into question the use of a word you can subtle destabilise any argument.

The truth is language is complicated and the english language is so steeped in history that it is one of the hardest to fully grasp and therefore easiest to manipulate. The meaning of words have been adapted so many times through the centuries that the original meaning doesn’t usually match its common usage. Debates end up being caught in details over language (or semantics). The game in debates is to attack weakness of understanding of words until you judge the right time to play the ‘simplify’ card. A debater will suddenly grab the confused and tired mood of the crowd and state the thought now running through most listeners heads:

“We can spend all day discussing semantics but at the end of the day this is all about people and all people need is…compassion. Compassion is not allowing suffering, therefore, assisted dying is the right thing to do”

No one will have the energy to argue the definition of compassion and it sounds plausible enough and, let’s be honest, we don’t have time to debate this anymore… To no one’s surprise, therefore, these staged debates always ended in a stalemate.

To be honest many of us don’t care as much about somethings as other people and so debates are often won by the most energetic arguers. To persuade others is more of a marathon of campaigning, slowly wearing opponents out. As victims of these campaigns it’s easy to tire and to give in rather than try and stand and engage.

Take the issue over Israel and Palestine for a moment:

Who has the right to the land of Gaza and the West Bank? We could start by going into all the history and legalities over this issue. The use of words such as ownership can then be brought into question. Historical facts could then be muddied by interpretation of events and phrasings and then there’s the insurmountable obstacle of personal stories and the tangled web of historical violence from both sides.

Who has the right to the land of Gaza and the West Bank? We could start by going into all the history and legalities over this issue. The use of words such as ownership can then be brought into question. Historical facts could then be muddied by interpretation of events and phrasings and then there’s the insurmountable obstacle of personal stories and the tangled web of historical violence from both sides.

Who started it? What were the real motives behind each attack? Who are the secret players behind the scenes, the hidden investors? We could easily end up just throwing your hands in the air and saying,

“I don’t know.”

It’s in this tired, apathetic position that you are a prime target for lobbyists with an agenda to come alongside you and gently and nicely persuade you to just subtly ‘understand’ their point of view. They say,

“I know, it’s complicated, right. All you need to know is… Israel are seeking complete control of their ‘Promised Land’”

or

“You just need to realise that… there was never a state of Palestine in the first place.”

The work of reconciliation, of bringing people into true understanding and real peace, is hard. In fact, I’d go as far as to say, it is humanly impossible.

In those school room debates the problem was that the point of the exercise was not to discover the truth but to win an argument at any cost. Success was judged not by the right outcome being found but a majority of people agreeing with you at the end. You didn’t have to be right; you just needed to be popular. I was always good at standing up, observing the room, and re-phrasing the emotions; twisting them and manoeuvring them to sound very similar to my motion and, therefore, encourage them to feel like I was speaking for them; I was a born politician. This, I soon realised, was a very useful tool in life. I could get what I wanted!

I discovered, however, that getting what I want isn’t always the best thing. I could manipulate anything except the truth. I didn’t know what was good for me, I still don’t. I don’t always know what is right. I had intelligence but not wisdom. The poverty of wisdom was always my (and I suspect all of our) undoing and I soon realised that building my life on intelligent manipulation of facts was like building a house on sand and it soon began to crumble and harm me. I had made decisions based on what I wanted. I had made my bed and now I slept in it. It was then, I was convicted of my lack of wisdom and found my need for God, the source of real wisdom.

The problem is I still have to wrestle with how much I argue about anything, particularly issues of faith, knowing that I have the ability and the sinful desire to ‘win’ at any cost. I am acutely aware of my own personal need for wisdom over and above intelligence and rhetoric.

Whilst on holiday I was enticed into a debate with a fellow traveller on the coach tour. The issues being debated were wide and various; the existence of God, matters of ethics, political discourse. It was tiring. I landed a few fine tuned points which won ground but ultimately it was a thoroughly unsatisfying encounter. Why? Because in the end both parties, him and me, were unwilling to listen. We didn’t seek wisdom, we sought success.

Winning arguments is easy if you can just wear down your opponent and the easiest way to do that is keep moving the goal posts; re-define the terms of the argument until it gets too complicated and they get confused and worn out. You don’t need truth to do this; all you need is stamina and intelligence.

Winning arguments is easy if you can just wear down your opponent and the easiest way to do that is keep moving the goal posts; re-define the terms of the argument until it gets too complicated and they get confused and worn out. You don’t need truth to do this; all you need is stamina and intelligence.

It is easy to look at the world with all the complicated issues brought out by relationships and be overwhelmed and confused. The instinctive position at this point is to succumb to the ‘live and let live’ view or the “there is no ‘right’ answer”. This is problematic when it comes to creating laws, governance and guidance as to how we live together. This approach only ends with lots of people doing what they like trying not to hurt others which ultimately won’t happen as we need to interact with each other; our personal desires will always conflict with someone else’s. The only way we can all be happy and not upset others is by not living together.

So how then do we live together?

Wisdom.

And how do we gain wisdom?

I want to suggest it’s ‘time’ and despite what many in our culture and society believe, we know we have time. God is a god of eternity. He is timeless, far above our concept of it. He holds all things in his everlasting existence. We proclaim that His kingdom will have no end. This means we have time; time to stop, time to listen, time to pray and invite God to work, time to wait for God to emerge and reveal Himself the source of wisdom.

Impatience and urgency are dangerous when making decisions. Yes, there’s a need for pragmatic decisiveness but should only be done in God’s timing.

Here’s where the General Synod has succeeded this week and where the House of Lord’s failed.

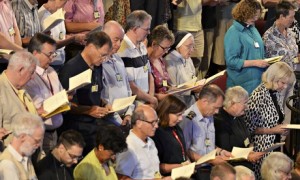

In November 2012 General Synod’s motion to vote female bishops failed, only just but enough. What was clear back then was that the debate had been established on the principle that there was an ‘us’ vs. ‘them’. The aim was not to discover wisdom but to ‘win’ at any cost. Both parties on the extremes didn’t seem to care how they would win just as long as they did. This week, however, the tone of the debate was not on winning points and persuasion but a genuine, heartfelt desire to seek wisdom and to trust one another. The debate stopped being about party politics but more about seeking genuine peace and wisdom only found in the Spirit of God.

In November 2012 General Synod’s motion to vote female bishops failed, only just but enough. What was clear back then was that the debate had been established on the principle that there was an ‘us’ vs. ‘them’. The aim was not to discover wisdom but to ‘win’ at any cost. Both parties on the extremes didn’t seem to care how they would win just as long as they did. This week, however, the tone of the debate was not on winning points and persuasion but a genuine, heartfelt desire to seek wisdom and to trust one another. The debate stopped being about party politics but more about seeking genuine peace and wisdom only found in the Spirit of God.

At Friargate Theatre back in May there was an evening entitled ‘The Stones Cry Out’ where two men from the Holy Land came and shared their stories. One was a Palestinian the other Israeli. Both men had lost daughters in the conflict and now they were travelling around together witnessing to the power of their relationship across the great divide.

The Palestinian father suggested the true route to peace is not to be pro-Israel or pro-Palestine but to be pro-peace. In order for real reconciliation and peace one must hold both parties in critical tension. To commit to both in equality and to be pro both and, at the same time, pro neither. This is not sitting on the fence! The problem with sitting on the fence is that the fence still exists. Real reconciliation is destroying the fence and stretching across to both sides.

To dismantle such a fence of division takes time, building trust and relationship something sadly lacking in our politics in this country. My very public critique of the Same Sex Marriage Bill was not based on some personal, moral judgement on homosexuality but on the way a decision was being sought. It was rushed. The lobbyists pressured opponents with the supposed lack of time and bullied people into making a response; to choose a side of the fence. Rather than taking the fences down they were happy to keep them there. People were forced off the fence onto one side or the other and it was all done by the manipulation of language. The same is being done with The Assisted Dying Bill.

To dismantle such a fence of division takes time, building trust and relationship something sadly lacking in our politics in this country. My very public critique of the Same Sex Marriage Bill was not based on some personal, moral judgement on homosexuality but on the way a decision was being sought. It was rushed. The lobbyists pressured opponents with the supposed lack of time and bullied people into making a response; to choose a side of the fence. Rather than taking the fences down they were happy to keep them there. People were forced off the fence onto one side or the other and it was all done by the manipulation of language. The same is being done with The Assisted Dying Bill.

When Lord Falconer was asked to give people time to engage and for a thorough exploration and facilitated discussion to take place he said there was no time. We need to make the decision now.

Why? Because he is afraid. He is afraid to wait. He is afraid of the suffering. He is afraid of what he might find when he stops and listens to the secrets of his heart. I sympathise with those who can see no hope in the future and want to take control of the confusion that surrounds them but the correct Christian response is to witness to our trust in the miraculous hope of God to bring peace and comfort. When all you have to look forward to is meaningless abyss then suicide may well feel like the best option; why wait?

We wait because, through the lens of Christ’s gospel we have lots to wait for.

Our gospel reading today calls us to deliberately and intentionally challenge our instinctive desire to act decisively ‘now’ to separate and divide; to judge ‘now’. God has time and so do we. God’s Kingdom will outlive every other lobbying group, political ideology and revolution. We are to look to Him for our wisdom not some human campaigner. This will mean we must exist in the painful complications of difference but it is in this field we call life that we grow. We live in peace when we accept God’s rhythm, God’s timing. Seeking relationships over and above position and power.

Peace is only achievable when we stop and let God work. To wait, often uncomfortably, in hope. This will often feel as if nothing will ever change, how it is is how it always will be but God waits for us to invite Him in and we should wait for Him to work. So let’s pray in God’s eternity for His hope and wait for His peace to rule.

…Ok. Since I wrote that reflection there has been a growing sense of some footing being lost amongst us. We have felt, at different moments, that we have lost our way or the passion has waned. This has been due to various small events in the life of our community which have combined to create not a destruction or a despair but a niggle, a question to arise: what are we doing?

…Ok. Since I wrote that reflection there has been a growing sense of some footing being lost amongst us. We have felt, at different moments, that we have lost our way or the passion has waned. This has been due to various small events in the life of our community which have combined to create not a destruction or a despair but a niggle, a question to arise: what are we doing? A wise brother amongst us wrote a deeply honest and profound response to my call for a discussion. He named the beauty of Burning Fences as ‘a clearing’. He writes,

A wise brother amongst us wrote a deeply honest and profound response to my call for a discussion. He named the beauty of Burning Fences as ‘a clearing’. He writes, This is our quest: to inhabit, together, No-Man’s Land. To share the space making no claim on it for ourselves or the parties, agendas and personal empires which we are tempted to enforce. We desire, however, to build our home there for to be at peace one must feel a sense of belonging. To what are we committing and how can that be spoken in this between place?

This is our quest: to inhabit, together, No-Man’s Land. To share the space making no claim on it for ourselves or the parties, agendas and personal empires which we are tempted to enforce. We desire, however, to build our home there for to be at peace one must feel a sense of belonging. To what are we committing and how can that be spoken in this between place?