If we wish to ask a favour of those who hold temporal power, we dare not do so except with humility and respect.

How do we pray?

At the end of this section on the Divine Office it is interesting that St. Benedict decides to end on the topic of humility. The chapter before this section was also about humility. It seems this is of the deepest importance to St. Benedict and is at the very heart of the Rule for community life. It has been this revisiting that has made me re-read my reflections on humility.

I still struggle with this. I wrestle in my inner life trying to work it out and allowing God to shape me free from my resistance. I am increasingly aware that one cannot do this work in isolation; one always needs a community around them to help in the practice of humility. This community must, together, commit to the work of supporting and holding one another as each one enters into the process of going deeper with God.

St. Benedict uses the experience of being in the present of humans who hold significant power and how, when we are with them, we are aware of our our own power (or lack of it). We naturally compare ourselves with one another and this is most definite when the contrast is large. It is only when the difference between us and others is clear that we are forced to acknowledge it to ourselves. It is in these times we know where we stand in the ‘pecking order’.

At the end of this week I will visit Archbishop John Sentamu of York. He has recently taken on the role as Episcopal oversight of the Deanery of York of which I am a part. He now is my bishop to whom I go to for clergy review, discipline and support. I have always really appreciated ++Sentamu’s ministry and we have shared many good conversations together. He ordained me both as a deacon and a priest and we have served together on the Step Forward conference run each year at Bishopthorpe Palace.

Despite having shared some social time together, as well as more formal occasions, I am always deeply aware of the weight of his presence and his authority. I may have questions or doubts as to how he uses that power but nonetheless I am acutely aware of his abilities to wield it both for good and (potentially) for bad. When we talk I rarely talk at great length due, in the most part, to my awareness of lack of knowledge and authority on subjects. On both legal, spiritual, theological and ethical matters ++Sentamu has more experience and expertise than I and should bow out of any debate. I did try once to argue that St. Aidan was to be given more credit than St. Paulinus and St. Augustine for the evangelisation of England… I tried but I think I failed!

This respect, forced or deserved, that I feel in the presence of ++Sentamu is not debilitating nor destructive of a relationship. As well as feeling inferior I also feel respected and cared for by him. My respect for him as a person is, I hope, mutual. I know he is interested in me and my ministry. I think he wants to see me flourish and wants to support me. I am listened to by him and, as much as he can, he looks out for me and holds me in some esteem. I am thankful for this relationship and thank God for our partnership in the Gospel.

St. Benedict uses this experience to portray our relationship with God. God is much more worthy of respect and awe than ++Sentamu. God alone is to be feared but, along with this fear there is also a deep sense of the safety and love God has for us, his children. When we go into his presence in pray we are to balance these emotions.

Some of us err, too much on the side of familial and breeze into God’s presence with conversation and chit chat. There’s nothing wrong with that. God loves to speak to us and have relationship with us but we should never take such relationship for granted. At times a colloquial relationship with God can lead to forgetting the heavy price paid for such a relationship which we should always be mindful of and thankful for. This awareness of the weighty grace shown to us should lead us into a deep awe and amazement at what he has done in order to have the conversation you so easily can have with him.

Others, however, err on the side of fear and trembling and see God so high and lofty above us that he remains distant from us with little affection between us. Christianity is unique in its understanding of God as, Abba Father. Jesus revealed a desire of God to be intimately involved in our lives like a good father is. Most religions see God as Creator and all powerful, and rightly so, but they miss out on that close and caring father image. Christians, following the example of Christ, emphasise this fatherly image because God has shown he cares for us by his death and resurrection.

God, in the Bible, is described as both a Lion and a Lamb. He is a lion because he is fierce and dangerous, ferocious. He is also known as a lamb, led to the slaughter, pastoral and innocent. The lion image creates in us a caution; no one would walk into a lion’s cage free from fear and respect but it would take something particularly peculiar for someone to be afraid of a lamb. Our approach to prayer and our relationship with God should be as C.S. Lewis describes it in his Narnia series. When the children enter Narnia for the first time, Aslan, the God figure in the series, is described by Mr and Mrs Beaver. Lucy asks whether Aslan is safe,

“Safe?” said Mr. Beaver; “don’t you hear what Mrs. Beaver tells you? Who said anything about safe? ‘Course he isn’t safe. But he’s good. He’s the King, I tell you.

The different kinds of prayers

I am aware of the different types of prayer that we participate in and yet we only use one word for them all. We say prayers in church services, and at Divine Offices. We pray alone, in pairs and in small groups. We pray out loud and in silence. We pray requests to God. We pray for discernment. We listen. We talk. We pray out of duty and we pray out of need. Contemplation is prayer just as much as extemporary, charismatic prayers. All of these have something different about them but they’re all called ‘prayer’.

It is wrong to suggest one is superior to another but equally it would be wrong to not use one type by telling ourselves they are all the same. To say, “I don’t pray out loud because it’s just the same as praying in silence.” leads you away from praying with others and sharing the public side of our faith; it would be like saying, “I don’t talk to my friend when other people are in the room.” It’s weird! In this chapter, St. Benedict is speaking specifically about prayers in the Divine Office. Philip Lawrence, OSB, Abbot of Christ in the Desert, suggests,

The admonition on short prayer in community comes from the way in which our ancestors looked at prayer. Quite often the saying of prayers was seen as distinct from the prayer itself. After saying a prayer, then one prayed in the heart and this was considered “prayer.” So in some of the early traditions, after each Psalm there was a short period for this spontaneous cry from the heart to the Lord. It is this type of prayer that must be kept short and pure–and not prolonged because it really cannot be prolonged. Attempts to prolong such prayer are usually just show and not reality. (Philip Lawrence, “Chapter 20: Reverence in Prayer”, Benedictine Abbey of Christ in the Desert, May 20 2014, http://christdesert.org/Detailed/890.html)

Reflection

I continue to reflect on the place of prayer in communities. I’d be interested to know if research has been done on how the frequency and nature of prayer changes a communities experience and understanding of God. I am currently part of two particular communities with very different views on prayer. One, my parish church, has a broad understanding of prayer and each member seems to have a different view on what it is and how it should be done. This emphasis is not bad and, as a minister and teacher in the community, it is part of my role to encourage people to develop their prayer life to all the different types of prayer. The other community is Burning Fences which used to read a liturgy from Celtic Daily Prayer from the Northumbria Community, at the end of our weekly gathering and now finds another kind of prayer. It was noted during a discussion last week that the inclusion of prayer has slowly morphed into a reflection on spirituality rather than a direct prayer. The place of prayer, i.e. talking directly to God, in Burning Fences is an interesting topic which we will need to raise as we move forward.

Abba Father, Glorious and Majestic Creator of the cosmos, I thank you for being my lion, defending me from foes and being able to fight for me the powers that seek to oppress me. I thank you also for being the lamb that was slain. I thank you that I can meet you in the Temple, where you sit on a throne high and lifted up and that I can meet you in the street, in the face of the poor and down cast, that I know you close by in my home and work.

Come, Lord Jesus.

…Ok. Since I wrote that reflection there has been a growing sense of some footing being lost amongst us. We have felt, at different moments, that we have lost our way or the passion has waned. This has been due to various small events in the life of our community which have combined to create not a destruction or a despair but a niggle, a question to arise: what are we doing?

…Ok. Since I wrote that reflection there has been a growing sense of some footing being lost amongst us. We have felt, at different moments, that we have lost our way or the passion has waned. This has been due to various small events in the life of our community which have combined to create not a destruction or a despair but a niggle, a question to arise: what are we doing? A wise brother amongst us wrote a deeply honest and profound response to my call for a discussion. He named the beauty of Burning Fences as ‘a clearing’. He writes,

A wise brother amongst us wrote a deeply honest and profound response to my call for a discussion. He named the beauty of Burning Fences as ‘a clearing’. He writes, This is our quest: to inhabit, together, No-Man’s Land. To share the space making no claim on it for ourselves or the parties, agendas and personal empires which we are tempted to enforce. We desire, however, to build our home there for to be at peace one must feel a sense of belonging. To what are we committing and how can that be spoken in this between place?

This is our quest: to inhabit, together, No-Man’s Land. To share the space making no claim on it for ourselves or the parties, agendas and personal empires which we are tempted to enforce. We desire, however, to build our home there for to be at peace one must feel a sense of belonging. To what are we committing and how can that be spoken in this between place?

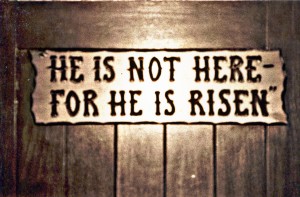

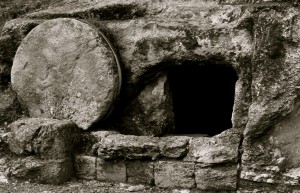

On Resurrection Sunday, I preached a sermon on the empty tomb and proposed that we can fall into the trap of staying at the empty tomb; we can get caught up in the empty tomb and be so amazed at it’s emptiness that we forget the real wonder of that day (This was an unashamed re-working of Thomas Merton’s reflection in his book ‘He Is Risen’). The empty tomb, I suggested, is just a signpost to the real thing. It is not the empty tomb we worship, it is the risen Lord. I likened this to gathering round a signpost for Yorkshire and celebrating as if we had arrived in God’s own country (I apologise to those heretics who do not accept this truth to be self-evident!)

On Resurrection Sunday, I preached a sermon on the empty tomb and proposed that we can fall into the trap of staying at the empty tomb; we can get caught up in the empty tomb and be so amazed at it’s emptiness that we forget the real wonder of that day (This was an unashamed re-working of Thomas Merton’s reflection in his book ‘He Is Risen’). The empty tomb, I suggested, is just a signpost to the real thing. It is not the empty tomb we worship, it is the risen Lord. I likened this to gathering round a signpost for Yorkshire and celebrating as if we had arrived in God’s own country (I apologise to those heretics who do not accept this truth to be self-evident!)