The night before I had sat with my generous host. He had worked all day with little sleep and had come late to be with me and share a cup of tea. Tea, in Pakistan, is as much a cultural icon as it is in England. There is, in parts of the country, a belief that you are not really befriended until you have shared three cups of tea with each other. Cup one and I am grateful for his hospitable heart towards me, a stranger.

We discussed the recent attacks on churches in Jaranwala. Attacks which had been a catalyst for me to come and visit. Attacks that opened my eyes to how fragile seeming tolerance between faith communities can be. Attacks which inspired the convening bishop, Azad Marshall, to be firm and gracious even at risk to his own life.

“How is it that many Pakistani Muslims in the UK rightly demand equality and freedom of religion and worship, and yet, once they have received it, do not offer the same courtesy to Christians back home?” my host had pondered.

The Jaranwala incident has clearly shaken the Pakistani Christian community. I know this as I have sat with brothers and sisters from Pakistan in Bradford and seen them wrestle with anger, fear and the desire to be faithful to Christ. Bishop Azad Marshall’s stance is clear: as Pakistani citizens, Christians want to know they are safe to live in their own land. This is resonant with other communities elsewhere across the globe. There is, however, not a call for revenge or retaliation in his communication. There is no bitterness towards the people who burnt their churches and Bibles and looted their homes. A simple but firm request for assurances that their lives are valuable.

I wake at 5am to a loud Friday morning adhan/azaan (the Muslim call to prayer) or it may be another liturgical proclamation. It is echoed across the city as muezzins seem to compete to be heard. I am thankful that my wife is not here and I calm my irritable tiredness and mutter my own devotions to God. I feel affinity with a neighbour in Bradford who in a moment of annoyance had complained that we rang our bell at the Cathedral at all hours of the day. I contemplate the challenge of contesting devotional practices in multicultural spaces and how interculturality should encourage a sharing of devotional rhythms whilst maintaining distinctive content to the worship. I drift back to sleep.

I wake again at 6.30am to loud bangs and rumbles. In the darkness I immediately assume it is gunfire and bombs. This same instinct is still present back home when unseasonal fireworks go off at odd times of the day. Here in Pakistan the possibility of warfare is slightly more plausible, and so I get up to investigate. It’s merely a much-needed thunderstorm which, rather than bringing death and destruction, brings lightness and the breaking of the dangerous toxic smog that has engulfed the east of the country. The Punjab region was put under a lockdown yesterday to protect further citizens contracting conjunctivitis from the polluted air. I thank God for his mercy and drop off to sleep again.

I jerk awake just before 9am cursing that my alarm was not set to go off on Fridays and I have missed morning prayer at 8am. I contemplate the consequences of this. No one is expecting me but how am I now to introduce myself to the college community in which I am staying? I acknowledge the irony of missing my own communal worship because the Muslim’s call to prayer had compounded my already disrupted body clock. I get dressed and decide to head to the chapel which doubles as classrooms and see what can be salvaged from the day.

I arrive to find people sitting in groups studying the Bible. I sit and ask God to direct me to a part of Scripture and I feel drawn to the book of Daniel. This is interesting bearing in mind last night’s discussions around interfaith relations with Muslims and reflections on being a minority faith amidst a majority population of a different creed. This is one of the aspects of my research on this trip: to explore what it feels like to be part of a minority faith community. In preparation for coming to Pakistan I jokingly added after telling people this is an area of study,

“…to prepare for the worst.”

My host had been realistic and disarming about the reality. Quoting Brother Andrew

“I was told that ‘one [man] and God is a majority.’”

I read in Daniel the story of a religious minority existing alongside people of different faith. Their witness to peaceable cohabitation whilst maintaining an integrity is freshly inspiring in relation to evangelism. I recall the same missionary approach by St Augustine of Canterbury. I return, again, to the conversation with my host.

What does it take to grow Christian communities in the context of being marginal and outliers? For my host it is focussing on discipleship, an intentional training of the small gathering of faithful people. When evangelism is denied (in the case of Pakistan, legally), a securing of the remnant is key and is seen in the story of Daniel in Babylon.

“Discipleship is always one on one, one by one.”

The stories told of the Pakistan Church facing a shocking lack of biblical literacy and doctrinal confidence is uncomfortably familiar.

“How are we to stand surrounded by a loud and popular religious culture if we are not tethered to our own conviction. This is why I start every conversation with Christians with one question, “Why have you chosen to follow Jesus?””

The use of the word ‘chosen’ is significant in Pakistan as the given religion is Islam. Is it so different in the UK? I have wrestled with this same instinct amongst the congregations I have served. What is discipleship without a choice to follow Jesus? This is not just in relation to the discussions around infant vs. adult baptism for the choice to follow Jesus must be daily. I long to have the mindset of these Pakistani Christians: to have to choose to be distinct and to hold firm to the belief in Jesus as the way of life, the truth of the world and the life to which I was made.

The response in Pakistan to the lack of basis of the faith has been to invest not in evangelistic mission but in teaching in order that wider mission can flow from it. I have long spoken of the UK not facing a missional crisis but a discipleship crisis. I now begin to think about how, in the wider, holsitic view of mission being the 5 marks of mission (tending, teaching, telling, treasuring and transforming) how slowly we have realised that teaching the faith is missional. Evangelists rightly call us to ‘tell’ and bemoan our lack of confidence to do so. There is something about Philip’s model of evangelism with the Ethiopean eunuch, which is both telling and teaching.

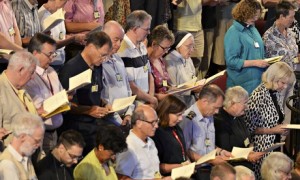

The General Synod of the Church of England will meet next week. I am suddenly grateful that I have limited access to the internet and will avoid the usual toxicity of Anglican social media. I contemplate on the state of my denomination. I pessimistically see the Pakistani Church as our future state and pray that, if we are called to be in real exile in our own land, I will be faithful and meet others one on one, one by one and be led by the Spirit to sure up the remnants of faith and tend to the needs of those I meet, tell them afresh the good news of Jesus Christ, teach them the faith as it has been historically handed down to me, treasure the gifts God has given to the Church and offers to them… but finally, I pray that I will, if called to do so, stand firm but graciously to see justice done; not as an act of subtle revenge on the perpetrators of injustice but to establish true justice. True justice being justice to both the oppressor and the oppressed.

I feel the shame of my lack of confidence to go and talk to others and sense their own reluctance to speak to me. The strangeness of social hierarchy baffles me afresh and I regret not asking for more formal introductions and structure to my visit. I sit in a class and pretend to follow. I notice recognisable words spoken.

“Taliban… masjid… Allah.”

If only I spoke Urdu better I could learn so much more from them.

Who has the right to the land of Gaza and the West Bank? We could start by going into all the history and legalities over this issue. The use of words such as ownership can then be brought into question. Historical facts could then be muddied by interpretation of events and phrasings and then there’s the insurmountable obstacle of personal stories and the tangled web of historical violence from both sides.

Who has the right to the land of Gaza and the West Bank? We could start by going into all the history and legalities over this issue. The use of words such as ownership can then be brought into question. Historical facts could then be muddied by interpretation of events and phrasings and then there’s the insurmountable obstacle of personal stories and the tangled web of historical violence from both sides. Winning arguments is easy if you can just wear down your opponent and the easiest way to do that is keep moving the goal posts; re-define the terms of the argument until it gets too complicated and they get confused and worn out. You don’t need truth to do this; all you need is stamina and intelligence.

Winning arguments is easy if you can just wear down your opponent and the easiest way to do that is keep moving the goal posts; re-define the terms of the argument until it gets too complicated and they get confused and worn out. You don’t need truth to do this; all you need is stamina and intelligence. In November 2012 General Synod’s motion to vote female bishops failed, only just but enough. What was clear back then was that the debate had been established on the principle that there was an ‘us’ vs. ‘them’. The aim was not to discover wisdom but to ‘win’ at any cost. Both parties on the extremes didn’t seem to care how they would win just as long as they did. This week, however, the tone of the debate was not on winning points and persuasion but a genuine, heartfelt desire to seek wisdom and to trust one another. The debate stopped being about party politics but more about seeking genuine peace and wisdom only found in the Spirit of God.

In November 2012 General Synod’s motion to vote female bishops failed, only just but enough. What was clear back then was that the debate had been established on the principle that there was an ‘us’ vs. ‘them’. The aim was not to discover wisdom but to ‘win’ at any cost. Both parties on the extremes didn’t seem to care how they would win just as long as they did. This week, however, the tone of the debate was not on winning points and persuasion but a genuine, heartfelt desire to seek wisdom and to trust one another. The debate stopped being about party politics but more about seeking genuine peace and wisdom only found in the Spirit of God. To dismantle such a fence of division takes time, building trust and relationship something sadly lacking in our politics in this country. My very public critique of the Same Sex Marriage Bill was not based on some personal, moral judgement on homosexuality but on the way a decision was being sought. It was rushed. The lobbyists pressured opponents with the supposed lack of time and bullied people into making a response; to choose a side of the fence. Rather than taking the fences down they were happy to keep them there. People were forced off the fence onto one side or the other and it was all done by the manipulation of language. The same is being done with The Assisted Dying Bill.

To dismantle such a fence of division takes time, building trust and relationship something sadly lacking in our politics in this country. My very public critique of the Same Sex Marriage Bill was not based on some personal, moral judgement on homosexuality but on the way a decision was being sought. It was rushed. The lobbyists pressured opponents with the supposed lack of time and bullied people into making a response; to choose a side of the fence. Rather than taking the fences down they were happy to keep them there. People were forced off the fence onto one side or the other and it was all done by the manipulation of language. The same is being done with The Assisted Dying Bill.