I continue to return to the question that remained unanswered by the speaker at the Anglican Network of Intercultural Churches,

Can you name a positive attribute of Englishness and a then name a negative attribute of Englishness?

Despite the ease with which, well justified, negative attributes came to his mind on ‘the English’ he could only find himself able to speak about the positive aspects of the establishment of the Church of England (interestingly he quickly undermined that by also listing the vastly more profound negatives!) The English in the room remained silent and there was no follow up. Maybe self-deprecation is the most English of cultural traits! Maybe, to be truly English is to always despise yourself more than anyone else (or at least to present as such) as a form of defence. The challenge comes when you are only left with the self-defeating narrative and it is only you who you are battling with.

As Bradford continues towards City of Culture it is this cynical, defeatist spirit of our age and culture which seems to be the most pressing and most powerful. How will our fortunes change as a city, let alone a nation, if we do not talk about our greatest threat: our own self-loathing? How do we avoid the historical pattern of falling prey to a counter, nationalistic fervour that has famously swept many other nations into the arms of totalitarianism?

As someone who works in the intercultural space, I am particularly aware of the need to be secure in my own cultural biases and lenses in order to engage in those of others. What this means is being able to explore and experience the cultural assumptions of others whilst remaining both objective and yet unthreatened by them. As part of my ongoing development, therefore, I have been exploring what it means, for me, to be ‘English’.

There have been a few books that have proven helpful. The most recent one is ‘England: seven myths that changed a country and how to set them straight’ by Tom Baldwin and Marc Stears. In this book James Graham, a British playwright famous for TV drama, ‘Brexit: The Uncivil War’ and the play ‘Dear England’, articulated the spirit of our age that I fear will rob us of the necessary imagination to reform our nation’s future.

Living in England for the past decade has felt like we were at the end of the TV series that just wouldn’t get to the end. It was financial austerity and the financial crisis too. Then, through the Scottish referendum through to Brexit – every relentless, exhausting, unprecedented week we were having – it just felt like everyone was pushing the button and the country just would not reset. People would not stop recommissioning this awful drama. People are trying to press the punch button but it’s just not reseting.

James Graham in, Tom Baldwin and Marc Stears, ‘England: Seven Myths That Changed a Country and How to Set Them Straight’ (London: Bloomsbury, 2024) p.233

We have a problem, we all can feel it, but we cannot agree upon the solution. I believe we cannot find the remedy because we have yet to clearly identify or articulate the real diagnosis. We know we’re sick; we just don’t know how or even why. A systematic approach to diagnoses starts with the ‘what’, discerns ‘how’ and discovers ‘why’. Once we’ve identified ‘why’, we can then discern the required treatment. Too often teams want to fix a problem and they waste time trying to treat the symptoms rather than doing the deeper work of discovering and curing the cause. This results in continued remissions and the subsequent time spent on managing the returning symptoms, albeit in slightly different forms.

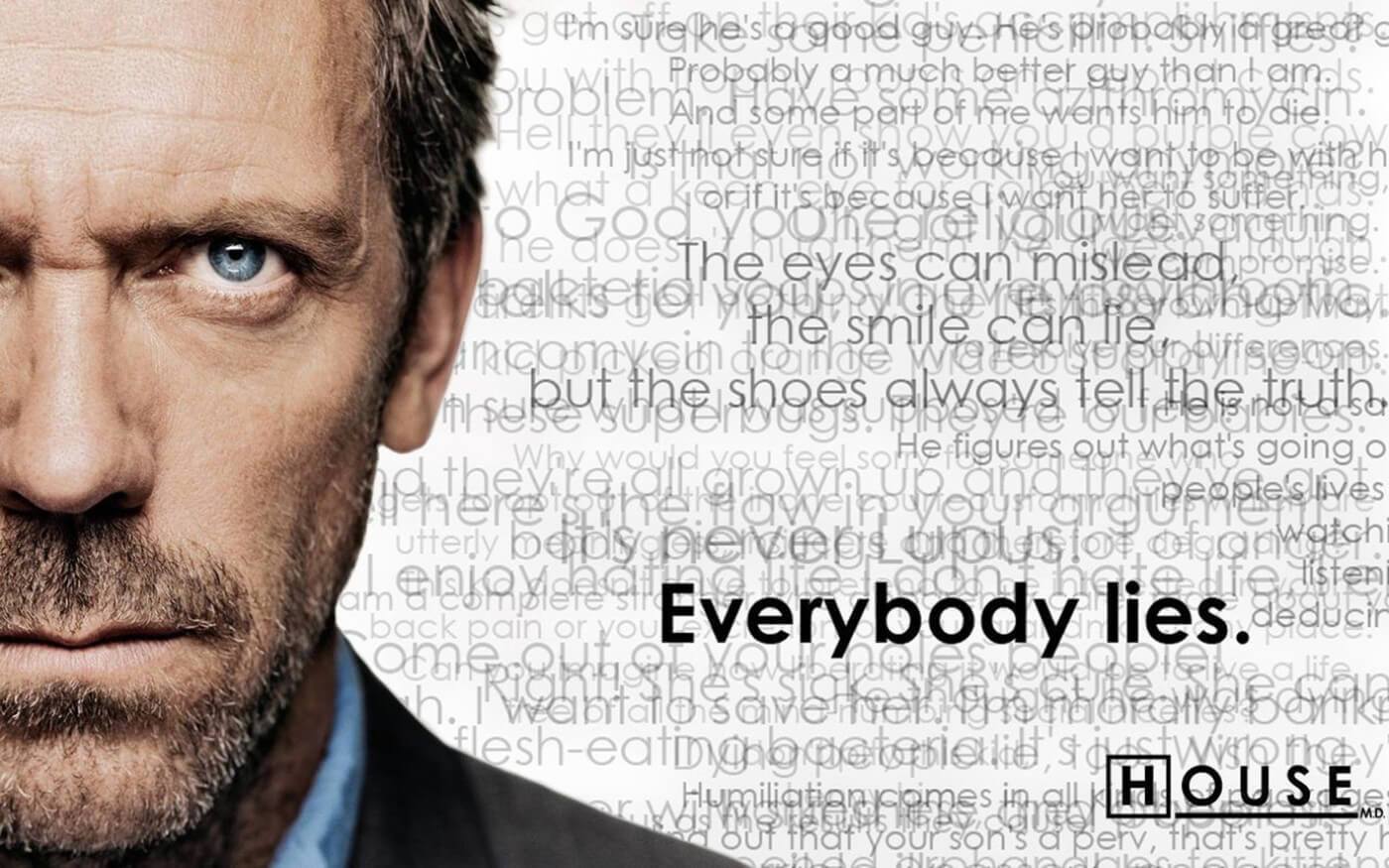

My conjecture is that we must take each presenting issue or symptom of ‘what’s wrong with this country’ and articulate how it has come to be so. This will require detailed study of the regression towards this state and to work out if this problem has always been the case (it may well have been). Once we have accurate, objective data on how this problem has arisen we can then turn our mind on why it has developed in this way. When there are multiple factors at work in a complex system like that of a whole nation this is harder to do and there is a need to apply practical experiments to navigate through the process of diagnosis. Like the fictional process in the American drama, ‘House’, there may need to be some brutal testing of theories to discover the true cure for the illness.

If we take this diagnosis process as a possible path to the right treatment we have two prior questions before we begin it: ‘who’ and ‘when’?

Who should be diagnosing? What group should be investigating and what skills/characteristics will be required within that group?

The second question, however, is key. How do we give such a group the necessary time and freedom to explore the differential diagnosis required? How do we gift them the time to research, debate and further interrogate options? In an age of increasing sense of urgency, the ‘relentless, exhausting, unprecedented weeks’ that our media culture now perpetuates for their own needs of ‘click bait’, this time is part of the solution.

When one is in crisis mode the natural tendency is to fight fires and those whose instincts and job it is to do that (managers) become the drivers of decision making.

We just need to do this before…

The issue “seems obvious” but then the solutions don’t work. This is where Gregory House’s cynical maxim comes in:

Everybody lies.

We tell different types of lies. I know, for example, I lie to myself when I am scared and lonely that I am misunderstood and overlooked. I then fixate on a solution and aggressively pursue it because I am unable to be truthful and vulnerable and admit that I don’t know. We all lie; to cover up our ignorance, indecisiveness and/or intolerance. It takes time and a boundaried space to bring those to the light and allow them to teach us about the deeper factors at play in situations. We, as a nation, have also lied to ourselves.

This is what was explored in Baldwin and Stears’ book about the myths of England. Their conclusion is that England is a complicated, contradictory country (much like Pakistan in Declan Walsh’s summations) and that we must always seek to gather all the information; accurately and thoroughly, being mindful that all information may be faulty in its presentation (“everybody lies”). Time, therefore, is required to interrogate and to do so with precision and focus.

This process is what is lacking in our politics and wider social conversations. This lack of creativity is a symptom, but one that is worth investigating. It leads me to consider what hinders creativity. I began to unpack this in a previous post ‘Into Culture: The Empty Space‘ and I have outlined in much more detail in my BA dissertation ‘The Divine Collective: how modern ensemble theatre practice can help establish creative Christian communities’. Primarily, the issue is common in groups/organisations/nations when they are under pressure; that of, fear and unprocessed grief.

I had wanted to write this month on the notion of patronage (maybe next time!) and about the social narratives/models that are available to shape our corporate identities. The selection of them is not straightforward nor without significant risks but there is a pressing need to find something that will help steer us in a new direction to health and prosperity.

In order to avoid the threat of totalitarianism, on the political right or left, we must defend ourselves against the temptation to myth making based on distorted histories and lies about ourselves. We must rightly diagnose the underlying causes of our intractable problems and avoid the knee-jerk, simplistic prescriptions that will only cure some of the symptoms whilst the disease goes undetected. In the end this will only lead to managing the pain as we enter into palliative care.

Don’t worry. I won’t leave us on that defeatist note. I started by saying I wanted to counter that! I do think there is an increasing appetite for big conversations. There is a renewal in the social patterns that encourage social cohesion. This increasing hunger for such cohesion bubbles underneath Bradford’s City of Culture conversations. How do we break the ground and allow the fountains of healing release to flow? How do we enable such deep diagnostic debate to occur and to ensure that we find the available cure in time? This is where the arts can, if they are allowed, play their part. Or, at least, that is the kind of art I’m interested in!