Suscipiendus autem in oratorio coram omnibus promittat de stabilitate sua et conversatione morum suorum et oboedientia.

Upon admission, in the oratory, before all, he is to make a promise to stability, conversion (of behaviour/morals/life) and obedience,

Conversion

I would not be a true writer on the Rule of St. Benedict if I did not begin by explaining that the latin term conversatio morum is a controversial phrase when it comes to true translation. What St. Benedict meant is lost in the dust of the original manuscript. I have decided to simply translate it as ‘conversion’ as most translations include this phrase; what changes is the object of that conversion (behaviour, morals, life, etc.) Thomas Merton famously wrote,

It is the vow to respond totally and integrally to the word of Christ, ‘Come, follow me’…It is the vow to obey the voice of God,… in order to follow the will of God in all things. (Thomas Merton, “Conversation Morum”, Cistercian Studies (1966) p. 133

Brian C. Taylor likens this vow to the repentance which is at the heart of the sacrament of baptism. This vow is a commitment to the ongoing turning away from sin and, more importantly the turning towards God.

We are regaining an increasing awareness that conversion is not a one time event. I know too many people who said ‘the prayer’ and were baptised and have since fallen away. The journey of faith starts in that first ‘yes’ to God’s call but there are many who never take many steps beyond that. Some treat the life of faith like a club; after they have paid the lifetime membership fee they find they no longer visit the club house, speak to other members. They keep the card in their wallet which they look at time to time but they do not participate in the life of the club, they do not remember the purpose of the club but their name is on the list.

The vow to conversatio morum is a life time commitment to participate in a process of change.

When you stop and think a little about St. Benedict’s concept of conversatio morum, that most mysterious of our vows, which is actually the most essential I believe, it can be interpreted as a commitment to total inner transformation of one sort or another – a commitment to become a totally new man. (Thomas Merton, The Asian Journal of Thomas Merton (New York: New Directions, 1975) p.337)

The first tension in the trinitarian of vows begins to emerge as you commit to stability and to change. A monk is pulled by seemingly opposing forces; one to remain faithful and one to move forward. Under the surface, though, these two vows hold a mysterious unity, a unity that develops as the two dialogue with each other. As you remain faithful to others you will be asked to change.

The commitment to conversion is a commitment to be open to discoveries about your failings and the sin that hinder your transformation into the likeness of Christ. We discover, as we decide to stay, particularly in painful conflict, that the only way that we can maintain stability is if there is change in our viewpoint. These two vows demand a moving through entrenched views on both sides.

There is also an important link between the vow of conversion and the vow of poverty which helps to deepen our understanding of conversatio morum.

Oscar Romero, when he was seeking unity within the archdiocese of El Salvador called all Christians to a shared understanding of conversion.

The criterion of genuine conversion was love for the poor, who represented Christ, and this love obtained forgiveness and grace from God. (Roberto Morozza Della Rocca, Oscar Romero: prophet of hope (London: Darton, Longman and Todd, 2015) p.120)

Christ is seen, for Romero, amongst the poor. It was Christ who considered equality with God not something to be exploited but emptied himself (Phillippians 2:6-7). Christ became poor so that we could be rich by God’s grace. If we are called to continually be transformed into the likeness of Christ then we should seek to also empty ourselves so that others may become rich by God’s grace.

All of us, if we really want to know the meaning of conversion and of faith and confidence in another, must become poor, or at least make the cause of the poor our own inner motivation. That is when one begins to experience faith and conversion: when one has the heart of the poor, when one knows that financial capital, political influence, and power are worthless, and that without God we are nothing. (Oscar Romero, The Violence of Love (Pennsylvania: The Plough Publishing, 1988) p. 121)

As I explore these vows I realise that not only is there an awareness of the Trinitarian shape to the life of a community committed to them but I’m also reminded of the other Trinitarian frameworks which I have discovered within my own monastic call. Here, in this quote from Romero, there is a call to place ourselves in a perpetual Ash Wednesday. We are dust, nothing but the life of discipleship is to remain rooted there whilst also accepting the conversion, by God’s grace, into Christ and receiving the power and anointing to become children of God by the Holy Spirit.

In this framework the call to stability is rooted in the faithfulness of God the Father who raises us from the dust to shape and form us. The call to conversion is brought about by the Holy Spirit who blows where it likes and brings about newness of life but points us to Christ of the poor and back to the foundational view that we are nothing. The conversion is also about being brought into true communion with others as one is converted through relationship and community. This exchange from the Ash Wednesday moment to the communal Pentecost moment rotates around a third point of reference: Christ’s obedience to death on the cross.

The Philippians 2 structure is also interesting when discovering this life within the Holy Trinity: we begin with the humility and awareness of our need for God. We remind ourselves, as we do at the start of Lent, that we are nothing. Without this awareness we will not fully understand the wonders of god’s faithful love and grace.

Let the same mind be in you that was in Christ Jesus,

who, though he was in the form of God,

did not regard equality with God

as something to be exploited,

but emptied himself,

taking the form of a slave,

being born in human likeness.

And being found in human form,

he humbled himself (Philippians 2:5-8a)

As we continually remind ourselves of our status without God we become obedient to his remoulding of us, his shaping of us. We submit ourselves to his will,

and became obedient to the point of death—

even death on a cross.(Philippians 2:8b)

Submitting to God’s will will lead us to death with Christ and we painfully obey that call in the hope that we will rise to new life. It is here that the start of conversion begins. The Holy Spirit begins its work of transformation and converts us into the likeness of Christ

Therefore God also highly exalted him

and gave him the name

that is above every name,

so that at the name of Jesus

every knee should bend,

in heaven and on earth and under the earth,

and every tongue should confess

that Jesus Christ is Lord,

to the glory of God the Father.(Philippians 2:9-11)

This conversion to ‘glory’ is not as most would imagine, an individual perfecting but the conversion is into the corporate Body of Christ who empties Himself to enrich the lost and the poor, not with material wealth but the riches of heaven. To be converted into this, therefore, is to particpate in that kenosis of God in Christ. This conversion into ‘something’ at once reminds ‘that without God we are nothing’.

Practical

So what might the call to conversion look like for the different forms of community?

Sodal

For those communities of more intentional belonging and activity the call to conversion maybe a relatively easy vow to taken on. Most of these communities are ‘new’ and part of the attraction of them is that they are fresh and different. These communities are born out of a desire for change from the mode. There is a temptation to stagnate, however, and the intial impetus fades. The response to these occasions is either to do something new or multiply. When multiplying though there may be a call to ‘not fix what isn’t broke!’ That which had embraced a call to bring about new things soon settles into a rhythm and tradition of its own. Trying to maintain both the call to stability and to conversion is a space, I think, which will bring about much fruit for sodal communities.

An ongoing question for sodal communities who adopt a vow to conversion as outlined above would be in what way are they converting and why?

For individual participants it will be about that inner conversion of opinions and behaviours. This must be done within the context of community in dialogue. This will be come into play at times of great discernment about directions or visions.

Why do I think or feel that is the right thing to do?

But the call to conversion also plays out on the communal aspects of life together too. Consider that point of stagnation into familiar, the plateauing of missional zeal and activity. How does the community continue to grow and develop whilst maintaining stability? The tension here is a creative one and will help steer discernment.

Modal

Parish churches are often parodied as the ultimate change resistors.

How many Anglicans does it take to change a light bulb?

Change? We don’t change!

This vow of conversion, the commitment to change, however, is at the heart of our baptismal liturgy. the issue is that the majority of our baptisms are to infants who are never encouraged to live out the continual conversion into Christ. This is why the baptism service must be performed within a main service in order ‘that the congregation… be put in remembrance of their own profession made to God in their baptism.’

Most change resistance within the parish church, I find, is about power. People get a status with positions of power. People connect that sense of control, prestige with what they do and so when someone challenges what is being done the individual takes it as a challenge to them. So Romero’s call to remind ourselves that financial capital, political influence and power are worthless is integral to bring about necessary change within a modal community.

The commitment to conversion, held within the tension of the vow to stability, is about the individual continual repenting of any claims on power and influence. It dialogues with the commitment to the rest of the community as you discern the will of God together in relationship. Yes, there are somethings that should remain but often asking the questions as to why reveals ulterior motives which will always need to be challenged within the context of repentance.

Nodal

As with the call to stability, nodal communities, particularly any New Monastic Society, the vow to conversion will be worked out in dialogue. All that has been said about having an openness to be changed by another is key in the nodal model. Conversion begins with the individual but develops into the communal and this evolution must continue into the networks of communities too.

Conversion could also remind distinct communities to remain connected with others as they seek to continual revisit their own life together. To dialogue with others who share this vow to both stability and conversion will mean that fruitful discoveries will be found. Sharing good practice, supporting one another, mediating for one another and ultimately challenging one another are many practical ways in which a nodal society can enable the living out of conversion across the communities.

Who has the right to the land of Gaza and the West Bank? We could start by going into all the history and legalities over this issue. The use of words such as ownership can then be brought into question. Historical facts could then be muddied by interpretation of events and phrasings and then there’s the insurmountable obstacle of personal stories and the tangled web of historical violence from both sides.

Who has the right to the land of Gaza and the West Bank? We could start by going into all the history and legalities over this issue. The use of words such as ownership can then be brought into question. Historical facts could then be muddied by interpretation of events and phrasings and then there’s the insurmountable obstacle of personal stories and the tangled web of historical violence from both sides. Winning arguments is easy if you can just wear down your opponent and the easiest way to do that is keep moving the goal posts; re-define the terms of the argument until it gets too complicated and they get confused and worn out. You don’t need truth to do this; all you need is stamina and intelligence.

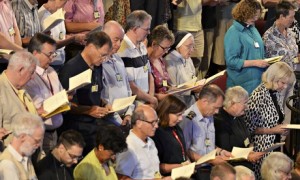

Winning arguments is easy if you can just wear down your opponent and the easiest way to do that is keep moving the goal posts; re-define the terms of the argument until it gets too complicated and they get confused and worn out. You don’t need truth to do this; all you need is stamina and intelligence. In November 2012 General Synod’s motion to vote female bishops failed, only just but enough. What was clear back then was that the debate had been established on the principle that there was an ‘us’ vs. ‘them’. The aim was not to discover wisdom but to ‘win’ at any cost. Both parties on the extremes didn’t seem to care how they would win just as long as they did. This week, however, the tone of the debate was not on winning points and persuasion but a genuine, heartfelt desire to seek wisdom and to trust one another. The debate stopped being about party politics but more about seeking genuine peace and wisdom only found in the Spirit of God.

In November 2012 General Synod’s motion to vote female bishops failed, only just but enough. What was clear back then was that the debate had been established on the principle that there was an ‘us’ vs. ‘them’. The aim was not to discover wisdom but to ‘win’ at any cost. Both parties on the extremes didn’t seem to care how they would win just as long as they did. This week, however, the tone of the debate was not on winning points and persuasion but a genuine, heartfelt desire to seek wisdom and to trust one another. The debate stopped being about party politics but more about seeking genuine peace and wisdom only found in the Spirit of God. To dismantle such a fence of division takes time, building trust and relationship something sadly lacking in our politics in this country. My very public critique of the Same Sex Marriage Bill was not based on some personal, moral judgement on homosexuality but on the way a decision was being sought. It was rushed. The lobbyists pressured opponents with the supposed lack of time and bullied people into making a response; to choose a side of the fence. Rather than taking the fences down they were happy to keep them there. People were forced off the fence onto one side or the other and it was all done by the manipulation of language. The same is being done with The Assisted Dying Bill.

To dismantle such a fence of division takes time, building trust and relationship something sadly lacking in our politics in this country. My very public critique of the Same Sex Marriage Bill was not based on some personal, moral judgement on homosexuality but on the way a decision was being sought. It was rushed. The lobbyists pressured opponents with the supposed lack of time and bullied people into making a response; to choose a side of the fence. Rather than taking the fences down they were happy to keep them there. People were forced off the fence onto one side or the other and it was all done by the manipulation of language. The same is being done with The Assisted Dying Bill.