I have given up on trying to sort my internal body clock and I lie in my bed attempting instead to consolidate my reflections. Putting aside the theological/missiological questions that have emerged during my conversations with Pakistani Christians, I return to my personal navigation in a foreign culture.

I am finding the lack of language a serious barrier. I walk around silently, loitering in the corners, creepily waiting to be approached. When someone does engage me in conversation, speaking beautiful English, I feel the need to respond in kind; in embarrassingly limited Urdu. I thus present as aloof. When I do speak English with them their understanding is not as full as I first believe and they look at me with such awkwardness and, worst of all, some form of humiliating deference. I just want to say “sorry” all the time.

I find social interactions challenging in my own culture with my own language and it takes me a huge effort to overcome that. I often overcompensate and feel as though I make people feel uncomfortable. I have no gauge as to the tone of conversations and have had so many painful experiences of misreading situations that, as I think of them now, my stomach scrunches up as though it were trying to hide itself further inside of me.

I have decided to make something of the day and attend some local classes for trainee clergy. I arrive, in my mind, just in time for Morning Prayer. No one is here. Pakistani’s, like other nationalities, do not have the same interest in time keeping as us Northern Europeans do. I sit on the opposite side of where I sat last time because, unknown to me, that time I sat on the women’s side. No one said anything, no one pointed this out to me. Why would they? Why wouldn’t they? Thinking back, I assume they were all laughing at my cultural naivety. Today I will do better.

The students who are leading prayers whisper together and look in my direction. I try to ignore them. When one stands up, he speaks in English to introduce the service. I shrink inside. Stupid English man can’t cope… I think about the practice I have adopted back home of saying “welcome” in any different languages that I know of spoken by guests. Is this what they feel? I am trying to make them feel welcomed and cross the barrier but here, on the receiving end, I feel an imposition.

Hello, paranoia, my old friend. I appreciate that you are trying to protect me and that you were invited to take your place inside my head after I realised that people don’t always mean what they say and that anyone, even trusted friends, can be hypocrites. They can pretend to be kind but they will soon disown you or abandon you when someone easier, more charismatic, less problematic comes along. I have tried to listen to you but, today you seem to have a lot to say.

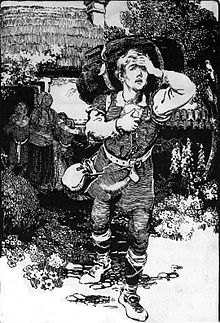

I am now sat in an English language class. It is strangely comforting to hear my own language. Although I am perfectly happy to be in a place and just listen to people talk to each other in Urdu with me not following a single word, it is nice to relax a little and be part of the community for a bit. I am embarrassed afresh as the exercises they are doing are at quite an advance level and I doubt many of us Brits would be able to do them. They begin to read ‘The Fir Tree’ by Hand Christian Anderson. Even those who seem to be struggling with English read it well, the teacher correcting mispronunciation. No one, however, notes my presence. When I make eye contact, people avert their eyes. I remember Mowgli in ‘The Jungle Book’ and remember that I am not one of them.

I haven’t had breakfast yet but they’re all going straight into Urdu class. Obviously, I need this class more than English but I am also unsure as to what is expected of me, so I go for food. The Urdu teacher asks where I am going.

“Naashtaa (breakfast). I am sorry.”

“Will you come back after breakfast?”

I don’t know. I imagine walking into the class halfway through and feel the eyes already burning into my soul.

“What are you doing here, Ned? You’re not learning anything, and you don’t understand a single word they are saying. At any moment they will ask you questions in Urdu and you’ll stutter and look pathetic.”

I say “yes” but have no intention of doing so. I hate my cowardice and leave.

Breakfast is sausage. The other guest has an egg on his plate. The hospitality team have clearly learnt.

As I eat I think about this blog and feel the self-enforced pressure to write something for today. I note my paranoid voice still wittering on in my head and then the voice that always drowns him out.

“I am a bad person.”

I call him, Neddyplod.

He is the voice of my younger self who was always so lost and confused as a child. The vulnerable boy who, no matter how much he tried, never quite fitted in. He has remained buried for many years, decades even, but, recently, since I discovered him on a walk, he has found some courage to be vocal. I am simultaneously grateful for his ‘bravery’ and yet burdened by his wounds. He carries so many accidental cuts and bruises from others who would be horrified to know what they did to him. He knew, even from the earliest days that they did not intend to hurt him but he had no language to express or ask for different treatment.

Here, in this new place, I am becoming Neddyplod again.

Writing this makes me cry. This is too raw. I need to write this, but does anyone need to read it?

“Attention seeking again, Ned, Neddyplod, whoever you are. You are going to post this though, aren’t you? Why? Because you want the affirmation. You want the prestige of being ‘brave’. You want to justify that ache inside you that craves what you missed out on as a child: acceptance.”

I am now thinking about plot structure. I am reading John Yorke’s excellent book, ‘Into the Woods’ which explores the nature of stories and how and why they work. All good stories have a ‘midpoint’.

…the midpoint is the moment something profoundly significant occurs…A new ‘truth’ dawns on our hero for the first time; the protagonist has captured the treasure or found the ‘elixir’ to heal their flaw. But there’s an important caveat… At this stage in the story they don’t quite know how to handle it correctly.

John Yorke, ‘Into the Woods: how stories work and why we tell them’(London: Penguin Books, 2014)p.37 and 58

I am at the midpoint of my trip and, although real life never fits story structure, might there be some treasure today?

Mowgli. A ‘man-cub’ brought up in the wolf pack as their own. He tries to pretend that he is not a human but a part of the pack but the book tracks his acceptance that he is different from the other animals and belongs elsewhere. The only trouble is that when he returns to humankind they do not accept him either. He is caught between. The story concludes with him making peace with his solitary existence as not neither one or the other but both.

In this place where I am different I am being made more aware of how different I am at home. Here, where there are clearer demarcations of difference (language, custom, clothes), I am tempted to long for home but, then, there’s the rub. There, where those differences are not present, I am still not the same. Where do I flee to?

I am tempted to say ‘my people’ are not here but nor are they there but, maybe, ‘my people’ are, somehow both.

I am comforted by Mowgli’s dislocation; his successes of adaptation; even his final torment at the in between place. This might be my elixir. I just don’t quite know how to handle it yet.