…if all this is to no avail, the abbot must wield the surgeon’s knife.

How do we reconcile?

It has not been easy to travel the last six weeks with the reflections on discipline, conflict and division. To have your prayer life shaped by the reading and meditating on such concerns, even hypothetically, causes a great burden to fall. I can’t wait until my prayers are shaped by utensils and hospitality but for now we must continue.

This week it is the heaviest of all the chapters on punishment. I will re-iterate a correction of the common understanding of excommunication for those of my readers who may have forgotten. Excommunication is not the total dismissing of a person from a community (well at least not in monastic life). Excommunication is aimed at being temporary and in this state the abbot still has contact and authority over the ‘wayward brother’; there is still hope of healing and a full re-instating. What is being discussed in this chapter, however, is the ‘surgeon’s knife’ (in another translation it is read as ‘amputation’).

I preached on Sunday about reconciliation, a theme the Lord continues to bring me to reflect on. I said in that sermon that I consider true reconciliation, the uniting of two parties with conflicting views and beliefs, to be humanely impossible. There is no argument or rationality that has ever changed someone’s deeply held convictions, those things that shape our identity. This is a matter of a spiritual shift; the work of reconciliation is a deep transformation down in the secret of all parties’ hearts. This takes time, trust and a transcendent commitment to the work of peace beyond rational thought and understanding.

There is obviously a human aspect to this work; the choice is left solely on the part of both conflicting parties to participate. This is understandable as all relationships are based on a free choice to be ‘bonded’ to another. If there was no freedom of choice then the relationship would not be genuine. Love requires freedom to exist. To be ‘re-bonded’ (which is what reconciliation literally means) requires that same freedom. Reconciliation cannot be forced upon anyone.

If we consider this in the context of peace talks between any warring parties at the moment (Israel/Palestine, ISIS/Christians, Russia/Ukraine) we can begin to see how purely rational, intellectual peace negotiations continual fail. Legislation which forces ‘peace’ is a fake peace and never a true reconciliation. What is required to encourage real reconciliation is a spiritual change on both sides; a commitment to attempt to freely choose to love. For humans who struggle to trust in the unseeable future, the miraculous changes in our spiritual core or the change of the lens through which we see the world, this reconciliation is impossible. We cannot imagine how we could ever trust someone who has hurt us so severely and so we resist. We begin the stalemate conversations of

They move first.

No They move first.

It seems strange, at first, to read in this chapter that it is after advice, the use of Scripture, excommunication and even the extreme: flogging that St. Benedict suggests

If even this has no effect, let him try greater things – his prayers and those of the other brothers – so that the Lord may cure the sick brother, for he can do all things.

There is a great realism here in how St. Benedict sees correction taking place. He knows, like us, that we will try all human avenues first (praying that they will work, of course) but in the end we must stop and invite God in to work in the place where only God can work. There will be times when the ‘sickness’ can be cured simply and we are encouraged to participate in that healing work through action. Then there is the time when all possibilities have been explored and you pass the patient onto the expert.

Anointing with oil

All of this makes me think about the role of oil in liturgical settings.

(bear with me)

The use of oil is a contentious issue and one that not many people think much about. There are specific occasions when oil is required: baptism, confirmation, ordination, healing and the Last Rites. The biblical understanding of anointing with oil is not clear. It is mentioned 20 times in the whole canon and there is a distinction between ordinary oil and ‘anointing oil’. This anointing oil must be kept holy and separate,

”It shall not be used in any ordinary anointing of the body, and you shall make no other like it in composition; it is holy, and it shall be holy to you. Whoever compounds any like it or whoever puts any of it on an unqualified person shall be cut off from the people.” (Exodus 30:32-33)

There are strict rules in the Law of Moses as to the use of this oil but in the New Testament there is very little mention or use of oil. The disciples use oil on the sick (Mark 6:13) and James, in his letter, advises its use on the sick too (James 5:14). God is said to use oil on Jesus in the letter to the Hebrews,

“Your throne, O God, is forever and ever,

and the righteous sceptre is the sceptre of your kingdom.

You have loved righteousness and hated wickedness; therefore God, your God, has anointed you

with the oil of gladness beyond your companions.” (Hebrews 1:8-9)

My understanding, having read both Scripture and Church History is that anointing oil is to be used on people who are to be set apart; that is why we do it at baptism, confirmation and ordination. The use of oil in the ministry of healing and preparation for death is to set the sick person under the complete care of God. The use of oil in healing ministry is to be done cautiously due to an overuse and, therefore, belittling of its symbolic significance.

James, in his letter, is clear that prayer for the sick is what will save them but he does encourage anointing. So which is it?

I would want to say that the use of anointing oil is symbolic of the complete handing over of a patient to the mercy of God. This maintains an honouring of medical professions and the human intervention on diseases. We can pray whilst attempting human medical support and God will honour that but there comes a time in illness when doctors cannot do anymore. This is, of course, a particularly sensitive issue at the moment and I will not repeat my view on the Assisted Dying Bill. It is at this time of the end of medical support that anointing is to be done. This could be done when the patient decides to no longer receive medication or at the point the doctors no longer offer any help.

Anointing becomes the physical ritual that marks the end of looking to humans for help and the naming of our full trust in God to act in this situation. This is not to say that we do not trust God when we seek human support, God uses humans in his work, but there comes a time when God must work the impossible; this, in the case of illness, is either to heal miraculously or to guide a person into the rest of death. I still believe that only God can do that leading and if we humans attempt to take that control we overstep ourselves and it is called murder/suicide.

if we look at St. Benedict’s thoughts on discipline then this final removal of a brother from the monastery is a death of one kind. This should be the absolute last resort and must be done with the greatest revelation of the wisdom of God. It should not be done lightly or without the handing over of the situation totally to God. The burden of responsibility placed upon the abbot cannot be overstated and the pastoral sensitivity in these cases is paramount.

If we take the analogy of choice in death a little further here, then I would suggest that it is not the choice of the brother or the abbot to break this bond between them but the choice of God and there must be that time of waiting for God to act in the situation. This time cannot be rushed and a great deal of listening must be done. A service where the brother is anointed would be an appropriate symbolic act and we wait, in the midst of that suffering, for the hope of God to be revealed.

Reflection

In all moments of reconciliation there needs to be a deliberate stepping into the mysterious, miraculous hope of God. Without this submission to transcendence real reconciliation, in my mind, cannot be achieved. It is a step of faith into the unknown which, from our side, is always into darkness. Hope and light will be found if two things are present; God’s mercy and care as well as the choice of the conflicting party. The mercy of God is trustworthy and true and can be relied upon. The free choice to participate from our opposition is more tricky. More often than not it requires us to submit anyway as a sign of our desire to be in relationship with them. This is a tough task and we resist it more often than not.

I want to pray for the big conflicts currently being played out in the world today. I pray for both Israelis and Palestinians that they would cease the cycle of violence. I pray for ISIS and the Christians fleeing Mosul that they would succumb to the peace and love of God. I pray for Russia and Ukraine that they would know the mercy and care of God and enter into the beautiful dance of community and peace.

Come, Lord Jesus

Who has the right to the land of Gaza and the West Bank? We could start by going into all the history and legalities over this issue. The use of words such as ownership can then be brought into question. Historical facts could then be muddied by interpretation of events and phrasings and then there’s the insurmountable obstacle of personal stories and the tangled web of historical violence from both sides.

Who has the right to the land of Gaza and the West Bank? We could start by going into all the history and legalities over this issue. The use of words such as ownership can then be brought into question. Historical facts could then be muddied by interpretation of events and phrasings and then there’s the insurmountable obstacle of personal stories and the tangled web of historical violence from both sides. Winning arguments is easy if you can just wear down your opponent and the easiest way to do that is keep moving the goal posts; re-define the terms of the argument until it gets too complicated and they get confused and worn out. You don’t need truth to do this; all you need is stamina and intelligence.

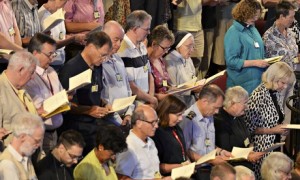

Winning arguments is easy if you can just wear down your opponent and the easiest way to do that is keep moving the goal posts; re-define the terms of the argument until it gets too complicated and they get confused and worn out. You don’t need truth to do this; all you need is stamina and intelligence. In November 2012 General Synod’s motion to vote female bishops failed, only just but enough. What was clear back then was that the debate had been established on the principle that there was an ‘us’ vs. ‘them’. The aim was not to discover wisdom but to ‘win’ at any cost. Both parties on the extremes didn’t seem to care how they would win just as long as they did. This week, however, the tone of the debate was not on winning points and persuasion but a genuine, heartfelt desire to seek wisdom and to trust one another. The debate stopped being about party politics but more about seeking genuine peace and wisdom only found in the Spirit of God.

In November 2012 General Synod’s motion to vote female bishops failed, only just but enough. What was clear back then was that the debate had been established on the principle that there was an ‘us’ vs. ‘them’. The aim was not to discover wisdom but to ‘win’ at any cost. Both parties on the extremes didn’t seem to care how they would win just as long as they did. This week, however, the tone of the debate was not on winning points and persuasion but a genuine, heartfelt desire to seek wisdom and to trust one another. The debate stopped being about party politics but more about seeking genuine peace and wisdom only found in the Spirit of God. To dismantle such a fence of division takes time, building trust and relationship something sadly lacking in our politics in this country. My very public critique of the Same Sex Marriage Bill was not based on some personal, moral judgement on homosexuality but on the way a decision was being sought. It was rushed. The lobbyists pressured opponents with the supposed lack of time and bullied people into making a response; to choose a side of the fence. Rather than taking the fences down they were happy to keep them there. People were forced off the fence onto one side or the other and it was all done by the manipulation of language. The same is being done with The Assisted Dying Bill.

To dismantle such a fence of division takes time, building trust and relationship something sadly lacking in our politics in this country. My very public critique of the Same Sex Marriage Bill was not based on some personal, moral judgement on homosexuality but on the way a decision was being sought. It was rushed. The lobbyists pressured opponents with the supposed lack of time and bullied people into making a response; to choose a side of the fence. Rather than taking the fences down they were happy to keep them there. People were forced off the fence onto one side or the other and it was all done by the manipulation of language. The same is being done with The Assisted Dying Bill.